The Orthodox Celts

by Fr. Deacon John-Mark Titterington

Orthodox Christians are bound by their own history to take a strong interest in Celtic Orthodox Christianity. In recent years there has been renewed interest in society as a whole in what has become known as "Celtic spirituality". Speaking generally, there seems to be a lack of interest today, however, in the other achievements of the Celts. Maybe this is because they did not build edifices which survived. After them came the Normans who erected enormous cathedrals and castles, as for example, at Durham, and this mark of permanence is reckoned to give them (the Normans) prestige in our times.

For the Celtic peoples, their "mark of permanence", if that is the right phrase, lies in people rather than buildings. Their great contribution to European culture and civilisation can be summed up in one word:- MISSION. They lived, and gave their lives, believing that "the Church is Mission". In no way were they confined to what is called the Celtic fringe of Cornwall, Wales and Ireland, and their missionary activities made them, in more ways than one, the founders of modern Europe.

The approach of the Celts to mission was thoroughly Orthodox. It began with a man, and sometimes a woman, experiencing a call from God; collecting some like-minded assistants and, following the guidelines laid down in the Gospels, just set off for distant lands with no change of tunic and knowing there was no possibility of a return to their homeland, preaching as they went.

The timing of these efforts was important. We heard last month of the break-up of the Roman Empire and how western Europe was left to defend itself. This it could not do and was soon over-run by pagan invaders who settled, in the case of our own country, like the Picts in the north; or the Angles in the north and east; the Saxons came into the south and the Jutes landed in Kent. One result of all these invasions was that the Christian church was pushed to the western fringes of our land which in the main, reverted to paganism and the history books often dub this period as "the Dark Ages".

But even barbarians settle down eventually and formed states, some larger than others, and helped by the residual Church and also by trade with other nations, became open to civilising influences. In this, by far the greater part was played by Celtic, largely Irish, saints and scholars.

The fifth century was a time of great upheaval on our shores but by the end of it, Ireland was largely Christian in a typically Orthodox way, which means that the bishop was a monk who lived in a monastery, where he was not usually the abbot, and so was himself subject to discipline. This organisation of the Church around monasteries, instead of around cathedrals, was to cause trouble and confusion later on, but at the time it suited God’s purpose admirably by providing a strong, well-educated and disciplined body of men (and women) who were able to go forth and make disciples of the nations of the earth. And that is just what they did.

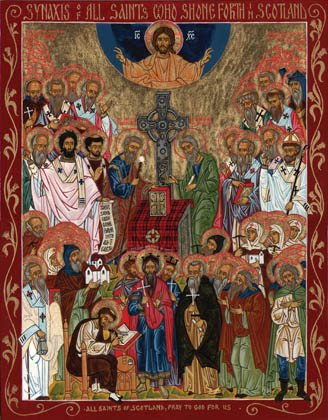

We are familiar with the re-evangelisation of our country after Colum Cille, or Columba, had founded the monastery on Iona and from there, had sent the monks into Scotland and across the north of England to Lindisfarne, which they made into a Holy Island, and the next base for their mission activities. From there, this part of the country heard the Gospel again under the guidance of Saint Aidan (died 651) and further south, later on, had their turn through the efforts of the brothers Cedd and Chad. So much is well known to us and we do right to thank God that it was so. And also, we can rejoice that at the same time, the Roman mission under Saint Augustine landed in Kent and began the evangelisation of the south in 597.

But Scotland, together with the northern half of England and Wales, is only a very small part of the total outreach of the Celtic Church. Their wandering missionaries went as far afield as France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Italy. Some monks went north to the Faroes and Iceland, and others found their way as far east as Jerusalem and even to Kiev in Central Russia.

Usually, the route to Europe was through Iona and Lindisfarne. Sean McMahon describes them as going into "the pagan land of the Franks by coracle against the stream of north-flowing rivers. Consciously following Christ’s example, these bands of determined men took little apart from precious religious books and objects. Land journeys were on foot unless they fell in with trade caravans. They journeyed until they found a location they felt suitable, hoped for a grant of a little land from a not unfriendly chief and set up their holy ground to the glory of God and (though it would not have occurred to them) the honour of Ireland." (Rekindling of the Faith page 14).

What did they bring? First and foremost, the fullness of the Catholic Apostolic faith as hammered out at the Ecumenical Councils, albeit with some trappings which were passing out of use in Western Europe by the end of the period. These were, as we have noted, the centrality of the monastery with a monastic bishop; a different way of calculating the date of Pascha and a strange way for monks to tonsure themselves. These apart, they brought a firm faith and with it sound learning and also an artistic approach, especially to the production of the scriptures by hand, which is still breath-takingly beautiful.

We are today hearing a lot about the formation of a united Europe. The first conscious attempt to establish this could said to have taken place under the leadership of the King of the Franks, Charles the Great, or Charlemange, who was crowned by the Pope on Christmas day in the year 800. To quote Sean McMahon again:--

"Charlemange ruled most of western Europe and was so noted as a lawgiver, administrator, protector of the Church and promoter of education that his court at Aachen was the centre for an intellectual and artistic renaissance. He invited the greatest scholars of the day to take part in his work, the most notable being Alcuin, of York, and the Irishmen, Clement Scottus, Dicuil and Dungal" (ibid page 31).

It is interesting that even today there is a building called "the Scottish Church" in the centre of the Austrian city of Vienna. It was originally founded by Celtic missionaries in 1156 and dedicated to Our Lady. From it a daughter house was established in the Russian city of Kiev, but that was abandoned in 1241 due to the invasion of the Mongols.

This indicates the extent of the influence of the Celtic Christians across the length of Europe and shows how the ministry of these wandering monks, gradually, over a period of about six centuries, helped to change for the better, the religious and cultural life of Western Europe and so prepared the way for what is rashly called "the new learning" of Dante and Erasmus. And they have been blamed for opening the doors which led to the so-called Reformation five hundred years later. But that is another story.

No comments:

Post a Comment